By John Christensen

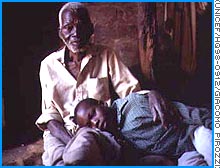

A man cares for his grandson, orphaned by AIDS, in a suburb of the eastern Zambia town of Chipata A man cares for his grandson, orphaned by AIDS, in a suburb of the eastern Zambia town of Chipata |

(CNN) -- In coming to grips with AIDS, the worst health calamity since the Middle Ages and one likely to be the worst ever, consideration inevitably turns to the numbers.

According to estimates from UNAIDS, an umbrella group for five U.N. agencies, the World Bank and the World Health Organization, 34.3 million people in the world have AIDS -- 24.5 million of them in sub-Saharan Africa. Nearly 19 million have died from AIDS, 3.8 million of them children under the age of 15.

Among the other statistics:

5.4 million new AIDS infections in 1999, 4 million of them in Africa.

2.8 million dead of AIDS in 1999, 85 percent of them in Africa.

13.2 million children orphaned by AIDS, 12.1 million of them in sub-Saharan Africa.

Reduced life expectancy in sub-Saharan Africa from 59 years to 45 between 2005 and 2010, and in Zimbabwe from 61 to 33.

More than 500,000 babies infected in 1999 by their mothers -- most of them in sub-Saharan Africa.

Finally, this: The bubonic plague is reckoned to have killed about 30 million people in medieval Europe. The U.S. Census Bureau projects that AIDS deaths and the loss of future population from the deaths of women of child-bearing age means that by 2010, sub-Saharan Africa will have 71 million fewer people than it would otherwise.

The numbers are staggering, but they do not begin to encompass the suffering and the dramas that put faces on the epidemic.

'We think we are animals'

|

A woman in South Africa wears a T-shirt bearing the name of a woman with AIDS who was killed by fellow villagers |

One face belonged to Gugu Dlamini, a South African woman who admitted on television on World AIDS Day that she had AIDS. When she returned to her home, she was beaten to death by fellow villagers.

Another belongs to a Ugandan girl named Kevina who lost both parents and her aunts and uncles to AIDS. Although just 14, Kevina must care for four younger brothers, three younger sisters and her blind, 84-year-old grandfather. They have no money, food, health care or transportation. Their roof leaks and other villagers sometimes steal their firewood.

"The teacher calls us orphans," Kevina writes in a letter published by the United Nations Development Program, "but I don't want that name. Even other children don't want that name. We think we are animals."

Increasingly sophisticated treatments have cut the death AIDS death rate in the industrialized countries, but elsewhere the epidemic is gathering momentum.

Infections in the former Soviet Union have doubled in the past two years. Journalist Patricia Thomas, author of a forthcoming book on the search for an AIDS vaccine called "Big Shot," says that "... in India and China, the world's most populous nations, their epidemics have just gotten off the ground."

The focus at the moment, however, is on sub-Saharan Africa, where 10 of the 11 infections that take place each minute occur, where in some countries teachers, doctors and nurses are dying faster than they can be replaced, and where treatment ranges from inadequate to non-existent.

A loaded word

AIDS was first identified in 1959 in what was then the Belgian Congo. Frank Vogl of Transparency International, which tracks corruption in governments, says that until the late 1980s "many African nations were in total denial. They thought we in the West were trying to fool them. They said, 'That's your problem. We've got other things to worry about.' I don't hear that rhetoric much any more."

Although governments are mobilizing -- including Botswana, Zimbabwe, Namibia and Swaziland where AIDS is the worst -- they sometimes take their own approach to the problem.

In South Africa, where one of every 10 people has AIDS, President Thabo Mbeki has confounded many by opposing the use of AZT, one of the most successful AIDS drugs, and by appointing an AIDS council that lacks medical researchers or AIDS experts.

"We know the government will intervene, and massively," says Dr. Robert Shell of the Population Research Unit at Rhodes University in Grahamstown, South Africa, "but the pandemic marches forward. Every day we get 1,700 new cases."

Factors contributing to the spread of AIDS include poverty, ignorance, the prohibitive cost of AIDS drugs, an aversion to discussing sex and, some say, promiscuity.

"Promiscuity is a loaded word," says Shell. "I would say that AIDS is a result of unsafe sexual practices, and unguarded sexual behavior is the most important factor. Ignorance about reproductive health is the biggest factor [and it] is related to poverty and illiteracy. Ten percent of the Africans in my province have other sexually transmitted diseases ...."

'Most men are not tested'

Many men leave their rural homes to work in mines and on

construction projects. This mobile work force and rapid urbanization has

contributed to cities in which 40 to 50 percent of the population has AIDS.

In a document prepared for the U.N. Development Program,

researcher Desmond Cohen writes that a 40 to 50 percent infection rate was

once thought "wholly improbable."

Wars have also contributed to the problem.

|

Two girls, who have been living with their blind grandmother since their parents died of AIDS two years ago, prepare a meal in the village of Nababirye in Kamuli District, northeast of Kampala, the capital of Uganda |

Like migrant workers, truck drivers and young men, soldiers

often visit "commercial sex workers," or prostitutes, 90 percent of

whom are believed to have AIDS. Nigerian soldiers with the ECOMOG forces in

Sierra Leone and Finnish soldiers serving as peacekeepers in Namibia took AIDS

with them when they returned home.

Girls and women are often forced to have sex with men in

male-dominated African cultures. In fact, says journalist Thomas, in some

areas infected men "believe they can be cured by having sex with a

virgin, and 12-year-old girls become infected."

The AIDS rate among women is much higher than among men, but

as Shell points out "most men are not being tested."

Meanwhile, they unknowingly may be passing on the infection

to African women. Compounding the problem, according to a U.N. study, is that

30 percent of young African women believe if a man looks healthy, he could not

have AIDS.

Strangling businesses

Given the variables and incomplete reporting on the epidemic, it is difficult to assess its economic impact with any precision. But there have been estimates that the per capita income in most sub-Saharan countries has declined by 20 percent.

|

Billboards carrying AIDS prevention messages are becoming more common in central Africa. This was one in 1995 in Zambia's capital, Lusaka |

The American Foundation for AIDS Research noted in a research paper late in 1999 that 80 percent of those dying are workers between the ages of 20 and 50 -- workers in their prime.

"AIDS is slowly strangling many businesses and economies," the report said, "and in a global market everyone eventually suffers."

Many companies hire and train two and even three people to do the job of one person because AIDS is certain to fell some of them.

The epidemic is also responsible for the quadrupling of life insurance premiums in Zimbabwe, escalating health costs to Botswana companies by 500 percent and driving the health costs of a large Zambian company so high that they exceeded profits.

In Zimbabwe and Botswana, where roughly one of every four people have AIDS, the disease has cut sharply into population growth with negative consequences.

"The zero growth is coming because people are dying in their young adult years, not after leading full lives and then dying," says Karen Stanecki, chief of health studies for the U.S. Census Bureau.

"People are dying in the years when they're supposed to be most productive, and they won't be there to raise the next generation. Which means you'll have all these orphans and no one to raise them."

The danger of global consequences

One of the most alarming speculations is that by the year 2010 there will be 40 million AIDS orphans in Africa, most of whom will have grown up with little or no social structure.

|

A girl orphaned by AIDS shares a floor mat with her foster mother who rests with a baby in their house in Mapete Compound in the town of Kitwe, central Zambia |

As much as humanitarianism, it is this vision of lawlessness and chaos and their potential to destabilize the global economy that has fueled worldwide concern.

"If we don't work with the Africans themselves to address these problems," U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Richard Holbrooke said in January 2000, "we will have to deal with them later when they will get more dangerous and more expensive."

Researchers are working on an AIDS vaccine, but such a medicine is still years away. In the meantime aggressive prevention programs can, and do, help.

A clever safe-sex campaign using catchy packaging and a suggestive slogan ("So Strong, So Smooth") turned condoms into a must-have item in Uganda. It also cut the AIDS rate from 15 percent to 9.7 percent. A vigorous program in Senegal has kept its infection rate at 2 percent

But African nations spend only $165 million a year to combat AIDS, and it all comes from the industrialized nations. James Wolfensohn, president of the World Bank, told the U.N. Security Council in January 2000 that an effective and comprehensive prevention program for sub-Saharan Africa would cost $2.3 billion a year.

To be effective prevention must be paired with investment that will create jobs, invigorate the educational system and pull the poor out of the "here and now" mentality that makes them susceptible to AIDS.

"Many of us used to think of AIDS as a health issue," Wolfensohn told the Security Council. "We were wrong. AIDS can no longer be confined to the health or social sector portfolios. AIDS is turning back the clock on development."

Says Vogl: "These countries have to make their economies grow. People who are trapped in poverty aren't going to do much about health care. If everything else in the country is falling to pieces, it is not going to have much effect."

(c)CNN-Interactive

|